First Patent Sets Maximum Patent Term for Later Patents under Obviousness-Type Double Patenting

Many patent applicants have received an obviousness-type double patenting (ODP) rejection at some time. For example, the U.S. patent examiner may reject the pending claims for being “patentably indistinct” from other claims already found in an issued patent owned by the same applicant. The examiner issues this ODP rejection even though the earlier-issued patent is not valid prior art for a regular obviousness analysis. However, the examiner further notes that there is still hope to gain allowance of the claims. The ODP rejection is typically followed by a statement that it will be withdrawn if the patent applicant files a terminal disclaimer with payment of the corresponding USPTO fee. While this offer sounds advantageous to the applicant, the final price for this patent will be paid in terms of shortened patent term several years later. While this story describes the traditional process of overcoming ODP rejections, a recent court decision, Allergan USA, Inc. v. MSN Laboratories Private Ltd., provides clarity for which circumstances would invoke the ODP doctrine.

For background, the United States grants two types of additional patent terms that extend beyond the typical 20-year patent term measured from the effective filing date: (1) patent term adjustment (PTA) and (2) patent term extensions (PTE). PTA is awarded to a patent when delays in prosecution are caused by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). On the other hand, PTE is awarded when regulatory delays are present, such as for drug approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. To prevent unjustified timewise extensions using the patent process, American courts developed a judicially-created doctrine to limit such unauthorized extensions, i.e., the ODP doctrine. Under the ODP doctrine, the courts determined that 35 U.S.C. § 101 requires that inventors may only obtain a single patent for an invention. More specifically, the ODP doctrine is based on a public policy that upon expiration of the patent, the public should be able to practice both the patented technology as well as any obvious modifications or variants.

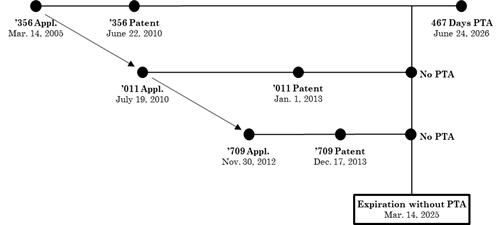

In Allergan, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) reversed an ODP invalidity analysis involving an applicant’s first-filed and first-issued patent and the applicant’s later-filed and later-issued patent. The Allergan court considered whether the later-filed and later-issued but earlier-expiring patent qualifies as an ODP reference for the ODP analysis against the parent patent. To understand the relevant ODP issues, reviewing the patent family timeline is very important. The parent patent is U.S. Patent No. 7,741,356 (“the ’356 Patent,” which is the first-filed and first-issued patent), which had two child patents, i.e., U.S. Patent No. 8,344,011 (“the ’011 Patent,” a later-filed and later-issued patent) and U.S. Patent No. 8,609,709 (“the ’709 Patent,” another later-filed and later-issued patent).[1] The patent family timeline is illustrated below, as reproduced from Allergan[1]:

As shown above, the ’356 Patent was awarded 467 days of PTA, while the ’011 Patent and the ’709 Patent were awarded no PTA. The ’356, ’011, and ’709 Patents are owned by Allergan through various subsidiaries. Subsequently, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Limited filed an Abbreviated New Drug Application seeking to commercialize a generic version of a drug covered by claim 40 of the ’356 Patent. Afterwards, Allergan filed a patent lawsuit that Sun Pharmaceutical’s drug application infringed the ’356, ’011, and ’709 Patents. Following an ODP challenge by Sun Pharmaceuticals, the district court declared invalid later-expiring claim 40 of the ’356 Patent under the ODP doctrine as being patentably indistinct from earlier-expiring claim 33 of the ’ 011 Patent as well as claim 5 of the ’709 patent. In other words, the district court invalidated claims of the first-filed, first-issued patent in view of claims of the later-filed, later-issued patents.

The Allergan court reversed the district court’s decision, holding instead that the ’011 Patent and the ’709 Patent are not eligible for use as ODP references against the earlier-filed, earlier-issued ’356 Patent. While previous courts had correctly established that a patent’s expiration date must include any awarded PTA in an ODP analysis, there was confusion regarding which claims could be used. Allergan noted that the intent of an ODP analysis is “to prevent patentees from obtaining a second patent on a patentably indistinct invention to effectively extend the life of a first patent to that subject matter.” Accordingly, later-filed, later-issued, but earlier-expiring patents would not improperly extend the patent term of the ’356 Patent. As a result, the Allergan court concluded that the ’ 011 and ’709 patents could not be asserted in an ODP analysis against the ’356 Patent. Stated differently, no claims of later-filed, later-issued, but earlier-expiring patents may be used in ODP invalidity challenges to earlier-filed, earlier-issued, but later-expiring patents because the earlier-expiring patents do not impact the term of the later-expiring patent in any way.

In view of Allergan, patent applicants now have many available strategies for maximizing patent term within their portfolio. For example, examiners often indicate that some claims with very narrow scope are allowable early in prosecution. Traditionally, patent applicants decided that a guaranteed patent having narrow scope of protection is better than risking any patent protection by continuing prosecution of the application. Under Allergan, patent applicants now have a clear incentive to put forth a reasonable effort during prosecution to obtain broader coverage in their first patent including any additional patent term that may be granted. Increasing PTA for the parent patent can further maximize the patent term for later members of the same patent family.

Another important consideration is that many ODP rejections should be traversed in the first office actions of child applications. Because the ODP law was unclear before Allergan, it made practical sense to file a terminal disclaimer in order to overcome an ODP rejection. Now, a simple legal argument based on Allergan may overcome an ODP rejection without necessitating the filing of a terminal disclaimer. The patent applicant may assert that the child application is unlikely to have a longer patent term than any issued parent patent and is thus ineligible to be used by the examiner as an ODP reference.

[1] Similar to the Allergan court, this article refers to applications leading to each patent by the associated patent number rather than by the application number. For example, the application leading to the ’011 patent is referred to as “the ’011 application.”