A Reminder that Written Description and Enablement also Require a Look Back in Time

Analyzing patent validity requires consideration of the circumstances at the time of the patent’s filing. For example, when deciding whether patent claims are invalid as anticipated or obvious, one must look at the available prior art and knowledge of a person of ordinary skill in the art available at the time of the patent’s earliest effective filing date. The recent decision In re ENTRESTO is a reminder that this timing perspective also applies to written description and enablement analyses.

In re ENTRESTO[1] is a recent decision of the U.S. Court of Appeals for Federal Circuit (“Federal Circuit” or “CAFC”) relating to a number of consolidated patent infringement actions filed by Novartis Pharmaceuticals against several generic drug manufacturers (“the Generics”) in response to the Generics’ filing of Abbreviated New Drug Applications (“ANDA”) seeking approval to market and sell generic versions of Novartis’s highly profitable and patented drug ENTRESTO®, which was developed in the early 2000s for treating heart failure.

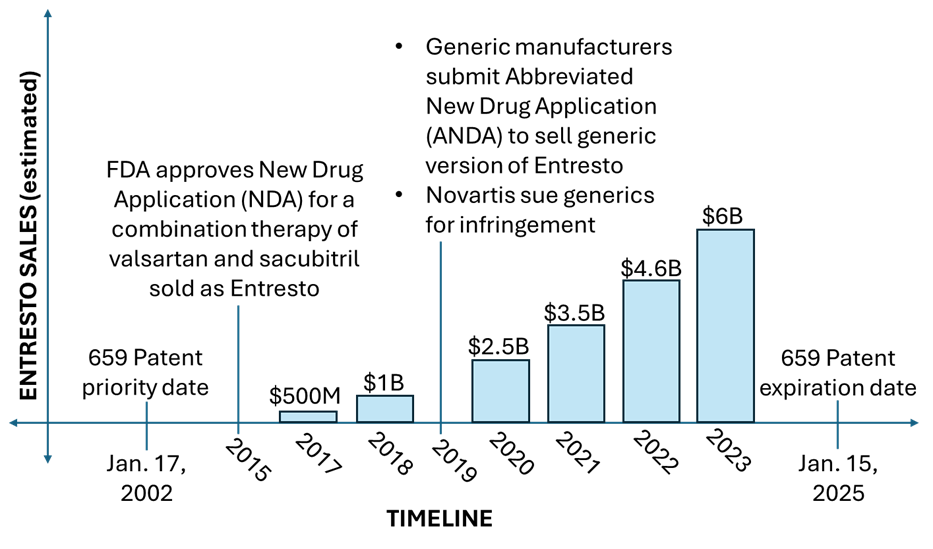

This case illustrates a common dilemma pharmaceutical companies face: the conflict between early patent filing and lengthy drug development. While filing a patent application early can secure a competitive advantage by preempting rivals, it often takes many years of further development and testing before a drug receives market approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. During the course of developing ENTRESTO®, Novartis filed multiple patent applications directed to incremental improvements made over the general concept of combining two types of drugs for reducing blood vessel constriction to prevent and treat heart failure. US Patent 8,101,659 (“the ’659 Patent”) is an earlier-filed patent in Novartis’s patent portfolio covering ENTRESTO®. Having an effective filing date of January 17, 2002, the ’659 Patent’s sole independent claim recites, in part, valsartan and sacubitril “administered in combination in about a 1:1 ratio.” As ENTRESTO®’s development progressed, improvements were found and later separately patented when valsartan and sacubitril were combined via non-covalent bonding to form a “complex.” Novartis didn’t begin marketing and selling ENTRESTO® until after the FDA’s approval in 2015. The ’659 Patent expired on January 15, 2025, just five days after the Federal Circuit’s decision in In re ENTRESTO. This timeline illustrates the relevant history:

The validity dispute concerned the claim term “in combination.” Both ENTRESTO® and the accused infringing generic products were “complexes” of valsartan and sacubitril (combined through weak, non-covalent bonds), rather than being formed as an unbonded physical mixture. The Generics first argued that the claim term “in combination” should be construed as limited to a physical mixture and excluding a “complex,” because the ’659 Patent didn't describe or claim “complexed” valsartan and sacubitril. In fact, valsartan-sacubitril complexes were not even discovered until four years after the priority date of the ’659 Patent. However, the court held that the term “in combination” should be construed according to its plain and ordinary meaning, encompassing both physical mixtures and complexes. In response, the Generics argued that such a construction renders the claim invalid for lacking written description and enablement.

To justify the grant of a patent, the patent must meet "minimum requirements for the quality and quantity of information" it discloses.[2] This is the policy basis for the written description and enablement requirements found in 35 U.S.C. § 112(a), which requires a patent's specification to "contain a written description of the invention, and of the manner and process of making and using it, in such full, clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art to which it pertains, or with which it is most nearly connected, to make and use the same." The patentee receives exclusive rights to exclude others from making or using the claimed invention in exchange for fully disclosing their invention to the public.

In ENTRESTO, the CAFC’s written description analysis examined whether the ’659 Patent adequately described the claimed invention of valsartan and sacubitril “administered in combination." Because the patent’s specification explicitly recited administering the claimed components “in combination,” the court held there was sufficient written description. The court explained that a valsartan-sacubitril “complex” was not specifically claimed, as such “complexes” had not yet been discovered by the time of the ’659 Patent’s priority date. Citing previous case law, the court stated that “[c]laim interpretation requires the court to ascertain the meaning of the claim to one of ordinary skill in the art at the time of invention.”[3] “Because valsartan-sacubitril complexes were undisputedly unknown at the time of the invention… the ’659 patent could not have been construed as claiming those complexes as a matter of law.”[4] Thus, the fact that the ’659 Patent did not describe a complexed form of valsartan and sacubitril did not affect the claims’ validity.

The CAFC further highlighted that while the invention claimed must be supported by the written description requirement, there is no requirement that the specification contain a written description of the accused infringing product. Accordingly, the proper analysis here includes first construing the claim, without reference to the accused infringing product, and determining if the construed claim is adequately described in the patent to meet the written description requirement. The same claim construction is then used to determine if the accused product infringes the claim. Thus, under a separate infringement analysis, a court would determine if the Generic’s valsartan-sacubitril complexes infringed the more broadly claimed composition of valsartan and sacubitril “administered in combination.”

The same result applied to the separate enablement requirement of 35 U.S.C. Sec. 112. The Federal Circuit confirmed that a patent’s specification need only enable any person skilled in the art to which the invention pertains, or with which it is most nearly connected, to make and use the claimed invention, not the accused infringing product. In this case, the court found that the accused infringing valsartan-sacubitril complexes included the claimed elements plus additional, unclaimed features that are part of a “later-existing state of the art.” The CAFC further held that this later-developed “complexing” feature, which was an argued improvement over the “basic” or “underlying” invention claimed in the ’659 Patent, could not be used to retroactively invalidate the claims.

Key takeaways: The written description and enablement requirements of Section 112 require describing and enabling the claimed invention as understood at the time of filing. Later developments or improvements, like the discovery of a complex form, do not retroactively invalidate a patent for lack of written description or enablement if the claimed invention itself was adequately described and enabled by the patent’s specification.